Let’s Learn about this together!

A dog stands on a newly mown lawn and you feel very safe that there is nary a worm larvae lurking.

But… that’s not how it works.

Some dog that you never met went potty on that lawn and the owner did not clean it up, or the owner cleaned up most but not all of it or the pup has diarrhea and so it could not be cleaned up.

Regardless of how it happens some poop gets washed into the soil with the rain. Then the eggs in the poo (if the dog has/had worms) hatch into larvae and these larvae crawl up the blade of grass to the top and when the top of that blade sticks up into the softy part of the foot [between the pads] it crawls into the blood stream (worm larvae call it between themselves ‘the subway’) and get out at the stop listed as the ‘intestines’, where they grow into adult worms. Yeah… I agree it’s like a Hitchcock movie but it’s really what happens.

Routine Fecal Flotation tests at the Veterinarian’s office are 70 % FALSE NEGATIVE

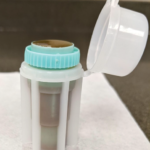

With these tests, some poop is mixed up with a solution and put in the above type container and a cover slip is placed on the device. Worm eggs float up to the top, stick to the cover slip and are then viewed on the microscope. IDEXX Continuing Education courses say 7 out of 10 people are told that the patient is worm free when they actually have worms. That’s what the phrase “70% False Negative” means.

There are a number of reasons for this: (1) The worms – just like chickens- may not be laying that day (2) Whipworms rarely lay eggs and so whipworm infections often go undetected (3) tapeworms segment off into little moving rice like pieces and so eggs are not found with tapeworms. (More about tapeworms later)

The first step many of us take when confronted by diarrhea is to bring a stool sample to your veterinarian to test for worms. That’s smart, because it’s very easy for dogs and cats who go outside to get worms. We are relieved when the sample comes back “negative,” meaning that no worm eggs were found in the pet’s stool. However, a negative fecal test does not mean that your dog or cat does not have worms; it simply means that no worm eggs were found in the sample.

IMPORTANTLY- DIARRHEA DILUTES THE POOP AND SO THE CHANCE OF FINDING EGGS GOES WAY WAY DOWN.

I’ll tell you a true story: At the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, it was not uncommon for us to see dogs and cats with chronic diarrhea. Because the owners were bringing their pets to a renowned teaching facility, they were not averse to doing fecal test after fecal test to check and recheck over and over for worms if their pets had diarrhea. Students were not allowed to say anything so I just stood and watched the below story unfold.

I remember one case of unresolved diarrhea in a young dog where we did at least ten fecal exams, about once a week with each visit. Each one came back negative, meaning that we saw no worm eggs when viewing the sample under a microscope. Weren’t we surprised when the owner came in with a plastic baggie of the roundworms that her dog had thrown up—after all those negative fecal tests- many months later!

Let’s look at it this way: I have chickens. If I go to collect their eggs and find some, I should be able to deduce that there are chickens present who have laid eggs in my henhouse. If one day I find no eggs, I can’t truthfully say that I have no chickens. They could have found an out-of-the-way place to deposit their eggs, or they could be having an off day.

Did You Know?

It’s very common for a pet owner to bring in runny diarrhea for the stool sample when his or her dog or cat has diarrhea. The diarrhea dilutes the stool sample and makes the eggs of intestinal parasites even harder to find.

Types of Worms and Bugs

Some of the common worms whose eggs can be found in a pet’s stool are hookworms, roundworms, threadworms, and whipworms. Infection with the protozoa Giardia and Coccidia can also cause chronic diarrhea.

Tapeworms are transmitted by fleas and do not produce eggs; rather, their segments break off and leave the body when they are ripe. These segments are found on the stool or around the anus but not in the stool.

Dogs can become infected with hookworms just by lying around at the dog park, watching the other dogs play. These parasites are called hookworms because they have hook-like mouthpieces that they use to attach themselves to the intestines. You see, a dog with hookworms relieves himself on the grass, and the eggs are transferred into the soil, where they develop into the larvae, which can survive for months before infecting your dog. These larvae can burrow right into your dog’s skin as he plays or lies down in the grass.

If your dog drinks contaminated water in the park, or if he grooms his paws after spending time outdoors and some larvae have come aboard, he can become infected with hookworms. Cats often get hookworms when they groom their feet. Hookworms can also be ingested by a rat or mouse, and if your cat eats one of those little fellows, she can get hookworms. However, hookworms are much more common in dogs than cats.

Once hookworms have entered your pet’s body, they travel through it like something out of The X-Files, winding up in the intestine. Without any GPS, they know just where to go. Once a pet gets hookworms, he or she can get not only diarrhea but also bloody stool and even anemia. Because the worms take a while to mature and shed eggs, initial fecal tests may show nothing.

Puppies and kittens are commonly born with roundworms. Female dogs and cats have encysted roundworm larvae in their body tissues. The hormones of pregnancy activate the larvae, which then migrate through the mother’s tissues and end up right in the uterus, infecting the yet-to- be-born puppies or kittens. The mother’s milk also transfers roundworm larvae to the nursing pups or kittens. In both cases, these parasites make it to the intestines of the youngsters to set up housekeeping. Because worming medications work only on intestinal worms, worming a female dog or cat before she becomes pregnant will have no effect on the larvae already encysted in the tissues.

Female roundworms can produce 200,000 eggs in just one day. The eggs are protected by hard shells, so they can exist in the soil for years. When dogs or cats groom their feet or happen to ingest infected soil or stool, the roundworms get into their systems and make their way to the intestines.

Whipworms are seen more commonly in dogs than cats. This worm sheds comparatively few eggs; therefore, multiple stool samples may not reveal their presence. If a dog has chronic weight loss and passes stool that seems to have a covering of mucus (especially the last portion of the stool that the dog passes), he may be infected with whipworms. Once again, Panacur, containing fenbendazole, is available over the counter and is safe and easy to administer as a powder on the food for three days.

FENBENDAZOLE FOR WORMING DOGS IS A POWDER IN THE FOOD FOR 3-5 DAYS AND THIS IS AVAILABLE AS PANACUR AND SAFEGUARD AND IS OVER THE COUNTER AT 1800 PET MEDS. I RECOMMEND ROUTINE WORMING TWICE A YEAR FOR ALL DOGS. YOU DO NOT NEED A DOCTOR’S SCRIPT TO GET IT HERE. IT IS A VERY SAFE PRODUCT COMMONLY USED NOWADAYS AS A CANCER CURE.

After reading about these different parasites, you may be ready to run to the heartworm preventives that have extras for treating intestinal worms or the flea and tick products that also promise protection from worms. I do not recommend that you do this. No pet needs so many toxins every month to protect against what a once-yearly worming with Fenbendazole will accomplish. Remember, we’re talking about minimizing toxic exposure.

Now you know how easy it is for your pet to get worms, and you understand that you can worm your pet if he or she experiences a diarrhea or GI problem, particularly if your pet is in situations where he or she is susceptible to picking up worms. I’m contacted often by people with pets who have diarrhea problems. You’d be amazed how many pet owners object when I suggest that we start with a simple worming treatment. “How could my pet get worms?” they ask. It’s easier than you think…and now you know why.

TAPEWORMS:If your dog has had fleas, he most likely got tapeworms as the Fleas carry tapeworm eggs. Fleas and tapeworms go together like a ‘horse and carriage’. They do NOT have to be crawling out of your dog’s tush. If your dog seems to be losing weight for no reason and he has had fleas within the last 3 years, consider TAPEWORMS. Tapeworms are common in both dogs and cats. Apparently, fleas think that tapeworm eggs are very tasty. Tapeworms are then transmitted to dogs and cats that ingest fleas. When you think of a cat grooming herself or a dog chewing away at an itch on his skin, you can understand how easy it is to ingest them. Another method of transmission is eating wildlife or rodents that have either tapeworms or fleas. Tapeworms can reach 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) in length within the pet’s intestine. Each worm may have as many as ninety segments, with the head at one end and many tiny brick-like repeating segments following. The segments farthest from the head detach. They come out in the stool and can be seen as little rice-sized pieces attached to the fur around the anal area. If you see what looks like dried rice on your cat’s favorite cushion, you’ve got tapeworms. Because these worms break into segments and do not lay eggs, a fecal exam will not show anything worthwhile. Tapeworms are also not killed by the typical worming medications that are used for the other intestinal worms. Panacur will kill certain tapeworms but is not very effective against the common tapeworm from FLEAS. Drontal Plus contains praziquantel, which effectively kills tapeworms. Tapeworms have a tough cuticle covering that protects them against digestion, and this drug dissolves that cuticle. In my practice, after treating with the recommended dose, owners would report that the tapeworms had returned. Because it was too soon for a new tapeworm to have developed and started to shed, I realized that the initial tapeworms had not been killed. You see, the heads of the tapeworms have thicker cuticles, which would protect them. That’s why, with tapeworms, I usually treat first with a dose of Drontal® Plus and follow it up with the oral tablet or Droncit about two weeks later. I like to feel secure that they’re all dead and gone. TAPEWORMS:If your dog has had fleas, he most likely got tapeworms as the Fleas carry tapeworm eggs. Fleas and tapeworms go together like a ‘horse and carriage’. They do NOT have to be crawling out of your dog’s tush. If your dog seems to be losing weight for no reason and he has had fleas within the last 3 years, consider TAPEWORMS. Tapeworms are common in both dogs and cats. Apparently, fleas think that tapeworm eggs are very tasty. Tapeworms are then transmitted to dogs and cats that ingest fleas. When you think of a cat grooming herself or a dog chewing away at an itch on his skin, you can understand how easy it is to ingest them. Another method of transmission is eating wildlife or rodents that have either tapeworms or fleas. Tapeworms can reach 4 to 6 inches (10 to 15 cm) in length within the pet’s intestine. Each worm may have as many as ninety segments, with the head at one end and many tiny brick-like repeating segments following. The segments farthest from the head detach. They come out in the stool and can be seen as little rice-sized pieces attached to the fur around the anal area. If you see what looks like dried rice on your cat’s favorite cushion, you’ve got tapeworms. Because these worms break into segments and do not lay eggs, a fecal exam will not show anything worthwhile. Tapeworms are also not killed by the typical worming medications that are used for the other intestinal worms. Panacur will kill certain tapeworms but is not very effective against the common tapeworm from FLEAS. Drontal Plus contains praziquantel, which effectively kills tapeworms. Tapeworms have a tough cuticle covering that protects them against digestion, and this drug dissolves that cuticle. In my practice, after treating with the recommended dose, owners would report that the tapeworms had returned. Because it was too soon for a new tapeworm to have developed and started to shed, I realized that the initial tapeworms had not been killed. You see, the heads of the tapeworms have thicker cuticles, which would protect them. That’s why, with tapeworms, I usually treat first with a dose of Drontal® Plus and follow it up with the oral tablet or Droncit about two weeks later. I like to feel secure that they’re all dead and gone. So now you know more about intestinal worms in dogs and cats than you ever wanted to know. As I treat so many cases of IBD and chronic diarrhea in dogs and cats, I find myself having to explain what I’ve told you above over and over again. Someday, this information may help you out and save you some time and expense. |